Originally published as Jabin T. Jacob, ‘Friend, Foe or Competitor? Mapping the Indian Discourse on China’, in Happymon Jacob (ed.), Does India Think Strategically? India’s Strategic Culture and Foreign Policy (New Delhi: Manohar, 2014), pp. 229-272.

Abstract*

This paper attempts to answer three questions: what is the content of Indian thinking on China? Who is it in India that thinks about China or is affected by China? And finally, how does thinking on China manifest itself in a strategic policy framework? The continuing lack of knowledge and expertise on China at a broad societal level in India has led to ignorance, fear, and prejudice about the northern neighbour. Further, the inability so far, to achieve a national-level closure on the brief border conflict of1962 – in the form of a consensus on what went wrong or who to hold responsible, for example – and indeed, the failure to achieve a resolution of the boundary dispute, have perpetuated a general tendency in India to ascribe malign motives to China and the masking of prejudice or ignorance under a framework of ‘realism’ in international relations. The work identifies three broad lines of Indian thinking on China are identified along with seven different kinds of actors or interest groups with varying degrees of influence on the country’s China policy. The consequences of Indian thinking on China are also examined through the use of examples from current policy.

China has always been independent India’s largest neighbour but it has not always been its most important neighbour. That privilege for a long time belonged to Pakistan on two counts. First, Pakistan was the representation of a competing and opposite philosophy of state formation, namely a nation justified by religion, and second, Pakistan was a security threat both in conventional terms and in the form of a supporter and instigator of secessionist movements and terrorism in India. However, it is debatable if Pakistan was or is ever actually seen as an existential threat to India, even as a nuclear power. Rather, it would appear that a belief exists in India that it could, if push came to shove, defeat Pakistan if things were to go that far. It is perhaps not just the record on the battlefield that justifies such a belief but something akin to a deep self-belief that India ‘understands’ Pakistan and its weaknesses as no other country can.[1]

As in the case of Pakistan, the study of Indian attitudes and views with respect to China, probably tells us much about the self-perceptions of Indians and their policymakers as they do about India’s China policymaking. In existential terms, China poses a different set of questions to India than does either Pakistan or the United States (the latter, an important comparison since it is the world’s sole superpower and as a democratic one, possibly a model India could aspire to follow). Even as it has become India’s most important long-term political and security challenge, the foundations of India’s strategic views of China are different from those of Indian strategic perceptions of Pakistan or of the United States.

When talking of Indian thinking about China, there are specific underpinnings here, of comparison between two ancient civilisations, between two developing nations and between potential competitors for regional and global influence. But the importance of the modern record on the battlefield – specifically, the Chinese defeat of India in 1962 – must not be underestimated either. The defeat has so deeply scarred the Indian national strategic psyche that it leads to some very real problems in categorising Indian thinking on China.

For one, views on China expressed in public by Indian government officials and by analysts involved in academic and policy discussions can be quite different from their views expressed in closed-door meetings and private conversations. While this might have something to do with natural processes of international relations, it probably has just as much to with a continuing lack of knowledge and expertise on China on a broad societal level in India – leading to ignorance, fear, and prejudice about China. In other words, compared to Pakistan, it is obvious that Indians lack the same level of ‘understanding’ or confidence in interpreting Chinese motives and actions; as close and familiar as Pakistan is to India, so distant and unfamiliar is China. Two, the inability so far to achieve a national-level closure on 1962 – in the form of a consensus on what went wrong or who to hold responsible, for example – and indeed, the failure to achieve a resolution of the boundary dispute, have perpetuated a general tendency in India to ascribe malign motives to China and the masking of prejudice or ignorance under a framework of ‘realism’ in international relations.

Given these conditions, this essay is a preliminary attempt to classify the Indian discourse on China not just with reference to texts and speeches in the public domain but also on the basis of the author’s conversations and interactions with individuals – retired and serving government officials as well as those outside government – and of experiences at and interpretations of meetings attended – bilateral and multilateral, academic and policy-related, semi-official and non-official – over a course of almost a decade in India, China and elsewhere.

This essay tries to answer three questions: what is the content of Indian thinking on China? Who is it in India that thinks about China or is affected by China? And finally, how does thinking on China manifest itself in a strategic policy framework? In the first section, three broad lines of Indian thinking on China are identified along with seven different kinds of actors or interest groups with varying degrees of influence on the country’s China policy. The second section examines how Indian thinking on China is operationalised in the form of policy while the third and final section briefly draws up the conclusions of this essay.

WHAT IS INDIAN THINKING ON CHINA? CAMPS AND INTEREST GROUPS

The Indian strategic imagination on China does not exist in a vacuum – it is influenced by views and pressures from within the country as well as those from abroad, primarily the West. This section highlights the primary lines of thinking on China in India and identifies the sources or interest groups in the country that contribute to thinking on China.

Three Kinds of Thinking on China

How is China perceived by Indians? The 1962 conflict is still fairly fresh in the Indian memory owing to the fact that many bureaucrats and soldiers who participated at various levels in that conflict are still significant voices in the Indian strategic debate on China. Many of this generation are unwilling to forgive or forget China’s ‘betrayal’ usually taking a maximalist position of China returning ‘every inch of land’ that was ‘taken’ from India – they form one major line of thinking on China. A second group in this generation, including the Nehru acolytes, may or may not be willing to either forgive or forget, but are ready however, to be more pragmatic and acknowledge the need for compromises given the fact that India is today in a qualitatively different position in terms of capabilities than in 1962 or the early 1980s (when boundary negotiations first started), or even 1998 (when India declared itself a nuclear weapons state). And while strengthening the Indian military could have been one of their original reasons to wait, this is no longer as important as the fact that its economic growth has resulted in a higher global political profile for India over time. A third group of individuals of this generation, comprising Nehruvians again, those with leftist leanings and many academics, have always been keen to enhance ties with China as a counter to Western-led imperialism. This group too, argues that compromise is necessary in order to achieve a boundary settlement. In the second decade of the 21st century, all three groups remain influential in political and policymaking circles as well as in forming public opinion.

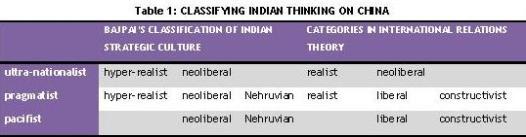

Members of each of these groups may be broadly termed ultra-nationalists, pragmatists and pacifists respectively for reasons of analysis.[2] This broad categorisation of Indian observers of China can do two things. One, it can place some thinkers identified by other scholars as belonging to different theoretical categories or schools of thought in the same group; two, it can separate others identified as belonging to the same category or school of thought. I argue that Indian thinking on China does not lend itself easily to a theoretical classification and that nor can any such classification be completely free of value judgment, given the current state of general ignorance and prejudice that exists about China in India.[3] The categorisation of Indian views on China into ultra-nationalist, pragmatist and pacifist is more relevant than other classifications attempted hitherto for a number of reasons.

One, there is a broad philosophy that can be identified as activating each camp – one could argue that the ultra-nationalists are driven by a worldview undergirded by resentment and a view of China as the ‘other’; the pragmatists, by a stress on the primacy of national interests and their achievability[4]; and the pacifists, by a belief that the developmental challenges facing India and China make good bilateral relations and regional and global cooperation between them imperative. Two, Indian thinking on any one country is precisely that – it is not Indian thinking on countries and states in general but Indian thinking on particular countries. And countries such as Pakistan and China apart from being far more important in the Indian imagination than others, can also often be analysed by the same Indians very differently.[5] Third, there is a difficulty in classifying strategic thought in international relations terms as opposed to behaviour – the former being more variegated, malleable, and ambiguous. Further, at this stage in Indian thinking about China, given the relatively small number of active thinkers, the large and increasing number of issues on which India and China are engaged, and the nature of the relationship – views and opinions remain fluid and/or unexpressed in public forums.

Therefore, while there will be variety within these three broad streams,[6] it is terms like ultra-nationalism, pragmatism and pacifism that I argue achieve greater accuracy in explaining Indian thinking on China. That they come with a certain value judgment is inevitable since it is one particular country that is being dealt with here and no one in India who thinks deeply about how to deal with China (and who are the subjects of examination in this essay) can make the claim that they do so without reference to a very particular kind of historical and political experience both as Indians and with China. Indeed, neither the sheer prejudice and vituperation against China (and Pakistan) or the persistent optimism about Chinese (and Pakistani) intentions vis-à-vis India – both important to the formation of views of China, and therefore, to policymaking on China – expressed by certain sections in India can properly be captured under such theoretical constructs as realists or liberals respectively.

Uniting all three strands of thinking is the acknowledgement of China as a rising power and a natural Asian and world leader that India is trailing at both levels and will do so for some considerable time. Taking on from this perception, all three parties agree also that national economic development is a key factor determining the size of the gap between India and China. All three camps consider China’s current political system an important basis for their understanding of the country but none consider it a serious possibility that India can influence or shape that political system in any substantive manner. The role of third countries – Pakistan, the United States, and Myanmar to name just a few – in affecting Sino-Indian ties is also acknowledged by members cutting across camp divides.

Ultra-nationalists

The views of the ultra-nationalists have a disproportionate influence given the widespread ignorance that exists in the Indian public about the circumstances of the Sino-Indian conflict in 1962, and about China, in general. The ultra-nationalists in addition to their wish to right historical ‘wrongs’ – the loss of Indian territory to China – generally believe that any compromises – with China would only hand it additional advantage and further weaken India’s regional and global position. In any case, China, this group argues, is not prepared to acknowledge India’s due weight in the world, preferring instead to keep India tied down to South Asia. Members of this group (like many pragmatists), believe that the 1962 conflict was the result of Chinese perfidy (and Jawaharlal Nehru’s mistakes), accuses the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of deliberately transgressing the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and expresses fears of a Chinese strategic encirclement (Chellaney 2012a; Adityanjee 2012). It is also this group that believes, that China is ‘unwilling’ to settle the boundary dispute and that Beijing sees India as a hostile power seeking to keep it off-balance regionally and globally (Dutta 2008; Stobdan 2008; Stobdan 2010; Roy 2011). In addition to expressing concerns over traditional security issues, worries are also expressed over Chinese behaviour on non-traditional security issues such as access to energy resources including hydrocarbons, and hydropower[7] (Chellaney 2011) and about the security implications of allowing Chinese companies access to critical sectors of the Indian economy such as power and telecom (Parthasarathy 2012).

This group comprises at least two sub-groups – Hindu religious right on the one hand and ex-government officers of either a rightwing persuasion or a hawkish predisposition towards China (and Pakistan) on the other.[8] The former sub-group is perhaps the least knowledgeable about China’s internal affairs (with the exception of goings-on in Tibet) or its foreign policy but this is in large measure irrelevant to their views of China given that their worldview itself is based primarily on the uniqueness and special place of Hindu culture and civilisation. The second sub-group is comparatively better informed about China and more capable of providing cogent policy recommendations to the government but still suffer from an inability to see China as anything but an unmitigated threat to Indian interests – discussions with members of this sub-group suggest that realism and prejudice mingle freely in their views of China.[9]

While the Hindu rightwing highlights the suffering of Buddhists in Tibet under the yoke of an atheistic and communist China (RSS; Advani 2010),[10] this support is somewhat contradictory, given this group’s general lack of empathy for the neo-Buddhists in India.[11] It also needs to be noted that Hindu rightwing concept of Akhand Bharat (‘united India’) on occasion includes Tibet within territories lost by India in the past.[12] Another standard issue raised by the ultra-nationalist camp is the China-Pakistan relationship and especially Sino-Pak nuclear weapons cooperation (Verma 2010).[13] A large number of this group also advocates closer cooperation if not an alliance with the United States for countering Chinese hegemony.[14]

Meanwhile, if it seems somewhat ironic that the religious right represented by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) forms a subset within the group of the ultra-nationalists, while its political face in the form of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been willing to modify their positions and been responsible for some major breakthroughs in relations with China[15] (and Pakistan[16]) while in government (admittedly a coalition government), then this suggests – at least in terms of India’s foreign policies, if not also in terms of its domestic policies – that there are pragmatists even within the religious rightwing.

Pragmatists

The pragmatists, meanwhile, without losing sight of the ‘challenge’ posed by China are not willing to engage in unnecessary scare-mongering about the China ‘threat.’ This leitmotif is evident when C. Raja Mohan (2009) says, ‘India needs a policy that is neither foolishly romantic nor stupidly hawkish’. Still sections within this group are on occasion, perhaps not above relying on the rhetoric of the ultra-nationalists and the public sentiments so aroused, as a negotiating tool both internally and externally. For example, it is possible that government officials could find it advantageous to play up the China threat in the interests of greater budget allocations for defence modernisation and/or infrastructure upgradation in border areas – both important in their own right but neglected due to apathy and low prioritisation by the political class. This is, however, no doubt, true of most governments around the world. Further, as will be discussed in greater detail below, such a strategy speaks of a technocratic or bureaucratic elite running China policy on the basis of objective conditions rather than with a view to changing those conditions one way or the other – something that in a democratic dispensation, only the political class has the legitimacy to do.

Broadly speaking, it is evident therefore, that a section each of the ultra-nationalists and of pragmatists can have similar realist views of China and its motives even as their rationales can differ. Pragmatists by nature will seek to ride on the coattails of increased attention to China – even if generated by misperceptions and misinformation – to achieve their ends.[17] According to B. Raman (2012), there is a debate ‘between a group of classical thinkers and a new generation of thinkers who perceive themselves to be forward-looking and visionary’. He noted that the latter ‘are even more worried about China than about Pakistan and want India to take not only the conventional measures… but even go far ahead by way of building up strategic convergences and co-ordinated thinking with other powers…’ (Raman 2012). According to Raman, this ‘new generation’ of strategic thinkers believed that the excessive focus on Pakistan had to be done away with and greater attention and resources needed to be diverted to dealing with China. The ‘classical thinkers’ however, disagree noting that unlike Pakistan, China has no historical enmity with India. While Islamabad’s constant aim is to ‘[keep] India weak and divided by constantly adding to its internal security problems,’ Beijing is only interested in asserting sovereignty over border areas such as in Arunachal Pradesh and stabilising Tibet against external interference. China according to the ‘classical thinkers’ has no interest in keeping India weak and divided (Raman 2012). There is thus a different viewpoint obtaining here about how Indian thinking about China might be categorised. Raman’s ‘classical thinkers’ while not being anti-China also do not seem to acknowledge structural realities in the regional and global order that might drive India and China apart and thus fall somewhere in between the ultra-nationalists and the pragmatists.

Pacifists

The China pacifists too, can consider themselves ‘pragmatic’ in their outlook towards China. The difference is that the pacifists do not hold an inherently suspicious view of China and are willing to act on the basis of present goodwill and of future opportunities from peaceful coexistence. They believe that despite tensions between India and China, there are also increasingly areas where the two countries can find common ground pointing out that the many challenges – internal and external – facing these countries will require joint efforts to combat. This group of thinkers on China also highlight the fact that India and China are today seen as capable of not only individually shaping the regional and global orders but of doing this together.[18]

While maintaining the liberal faith in the importance of global institutions, the pacifists are also conscious that many of these institutions are dominated by the West/the United States and are wary too of Western attempts to subvert cooperation between India and China (Varadarajan 2011; Varadarajan 2010). Thus, Indian actions such as being part of the ‘quadrilateral alliance’ against China or Indian ambitions of being a ‘balancer’ in Asian power politics have also been criticised by members of this group (Bhadrakumar 2009). Of course, this position and others in general of the pacifists can be perceived by members of the ultra-nationalist and pragmatic camps as being dogmatic or plain impractical.

Those with pacifist leanings belonging to the Left parties, while not necessarily China specialists, also support peaceful and cooperative Sino-Indian relations including against Western hegemony, but attract almost immediate criticism especially from the ultra-nationalists because of their political identity and the role of the Indian Left in general, during the 1962 conflict.[19] Meanwhile, non-Left leaning pacifists – usually Gandhians and civil society activists – as of now are usually more interested in issues connected to India-Pakistan ties than Sino-Indian relations. While the constant peril of externally-sponsored terrorism in India over the decades and of an extremely volatile neighbourhood coupled with the limitations imposed on effective Indian action owing to international constraints appear to push this group of pacifists increasingly into a minority, the simultaneous rise of India and China ensures that the China pacifists will remain a significant group influencing Indian views and policy on China.

Seven Actors in China Policy Formulation

The three camps outlined above are each now dominated by a mix of current and former government (civilian and military) officials and academics with journalists and a growing number of researchers in think-tanks who straddle the space between government and academia. But on the whole seven actors or constituencies may be identified as influencing China policy in India to varying degrees. These include government officials both retired and serving, journalists, think-tankers, academics, political leaders, business interests, and the general public.

Government officials

Among government officials both retired and serving, as is the case anywhere else in the world, there are differences of opinion between civilian bureaucrats and military officials. While this tension is not easily visible in the public domain, retired officials from both streams, particularly the latter, have been less chary of expressing their views and differences in public. While civil-military relations in India are certainly more amicable than has been the case in its immediate neighbourhood, there have certainly been strains in this relationship. Nowhere was this more evident than in the conduct of Indian operations in the run-up to and during the 1962 conflict with China.[20] Coming to the present, it would appear that both sides have broadly pulled together on China-related issues (in comparison with say issues related to Pakistan) and it would not be incorrect to say that government officials today of both varieties belong largely to the camp of the pragmatists.

It is important to note however, that in the case of those out of government – both civilian and military – the large majority tend to be extremely critical of the government’s policies on China (as also on Pakistan and the United States and other subjects). This suggests at least two possibilities. One, there are internal divisions within the bureaucracy when it comes to China policy; and two, there is lack of political direction on China policy. Given that the criticism is usually in the form of the government not having been aggressive or assertive enough in its dealings with China,[21] this suggests that it is usually the pragmatists – with a keener sense of what is and is not possible vis-à-vis Beijing – who win the arguments on China policy. It is assumed that it is not the pacifists that are winning the argument, since one, New Delhi’s policies continue to reflect a wariness about greater engagement with and identification with China and two, India’s military modernisation has rapidly picked up pace in the post-Cold War era – a modernisation that is now increasingly framed in terms of a necessary response to the challenges, if not threat, posed by China’s own military modernisation (and the Sino-Pak nuclear alliance).

However, in studies of Chinese infrastructure development in Tibet, there is also implied criticism, especially from retired military officials that India is not doing enough or has been too late by way of upgrading physical and military infrastructure in the border areas facing China (see Anand 2012; Rajagopalan and Prasad 2010; Chansoria 2011). This in turn suggests a divide between civilian bureaucrats and military officials and there have been on occasion attempts, in public fora, by one side to affix the blame on the other – once again, a result no doubt of lack of political leadership in the framing of policy and in mediating intra- or inter-institutional conflicts.

Journalists

Journalists have always been a small but prominent group when it came to discussion of foreign policy in the public domain.[22] In the age of 24×7 television news however, while the volume of news on international affairs has increased, it has not meant a corresponding increase in the quality of that news. Journalists with in-depth knowledge of China and hence, a nuanced understanding of its foreign and security policy motivations, are however, difficult to find. Those who come up with an informed analysis of Chinese motivations are usually those with some academic training in international relations and international political economy, and hence, do so on the basis of an entirely different skill-set.

There has been a marked difference however, in the quality and influence of the media on matters of foreign policy. In an earlier age, dominated by the print media, each newspaper had a few key correspondents who provided both news and analysis with the occasional contribution from either government or academia. Today, however, the expansion of the media – in particular television media – has meant that previously unnoticed or insignificant transgressions of the LAC between India and China make for immediate headlines.

Further, 24×7 news media like nature, abhors a vacuum. Given that expertise on China – as indeed, on any number of foreign policy issues – has historically always been low in India and that correct information and exact details on the boundary dispute have been unavailable given government policy, this vacuum is more likely than not to be filled by misinformed and confused analysis by everyone ranging from retired civilian and military officials to socialites, and especially on television, and usually ultra-nationalist. Either way, the power of the media to influence public opinion and thus possibly, force the hand of government, cannot be discounted.

Foreign policy and strategic affairs think-tanks

At foreign policy and strategic affairs think-tanks, which are of fairly recent vintage in India, the personnel is split rather sharply between retired or in-service civilian and military officials on the one hand and academically-trained researchers, often fresh out of university, on the other.[23] The former bring with them experience as well as points of view not easily available in a purely academic environment. Researchers meanwhile, combine their frequent exposure to government circles or government at one remove (in the form of retired officials) and their academic skills to produce research geared towards policy-making or policy-influencing. While this group is nowhere near as good as it should be on China-related matters, it is getting better with more academics having the opportunity to travel to China or to study the Chinese language and is likely to be increasingly influential in foreign policy circles along the lines of their counterparts in the US, or for that matter, China.

At the same time, there is the suspicion expressed by retired government personnel – which no doubt, also mirrors those of personnel currently in service – that think-tanks reflect the agenda and interests of their funders. Given that these funders are in many instances foreign institutions, the implication is that these think-tanks are not to be trusted. The idea of think-tanks functioning with an independent agenda either because they draw funding from multiple sources or because of the force of their leadership or both, does not seem to pass muster with these skeptics.

And it is not as if fully government-funded think-tanks such as IDSA, ICWA, CLAWS, NMF or CAPS produce a quality of work that sets them apart from either other think-tanks in the country or those abroad. Despite being supported by the government, these think-tanks do not always have the greatest access to current government thinking leave alone the possibility of their policy recommendations being adopted. This in turn suggests a protection of turfs by government agencies and interests and an unwillingness to listen to possibly better-informed views and analyses in the interests of producing good China policy.

Academics

Academics form another major group of actors in the formulation of India’s China policy. Jawaharlal Nehru University’s (JNU) School of International Studies and Delhi University’s Department of East Asian Studies together remain the primary sources of academic expertise on Chinese government, politics and foreign policy in the country, which is not to say that they are also simultaneously successful in providing quality expertise. In the past, at least a few academics were closely linked to the political establishment and therefore, had direct access to influential decision-makers in both the bureaucracy and the political classes. In part, this was also the result of the much smaller world of foreign policy thinkers existing at the time of Indian independence and in part, because both academics and the policymakers often shared the same class backgrounds, forming part of a tiny English-speaking and worldly-wise elite. Today, some academics continue to be influential in Indian government circles but the numbers and tasks of both bureaucrats and academics have increased in a manner that does not always allow the two groups to interact more frequently and more closely. Academics today can receive either formal recognition with positions on governmental advisory boards[24] or informal access to information but on the whole, as far as China is concerned, such interactions between academia and the government are limited and show no visible impact on one or the other.

Meanwhile, in an age of market incentives and increasing global interest in the Sino-Indian relationship, there is a growing acknowledgement within academia of the need to produce greater policy-relevant research on China and Sino-Indian ties, in addition to research on traditional areas of focus. This is in no small part being encouraged also by the demand from the government and think-tanks as well as the greater resources now becoming available to universities. Thus, quite a few scholars from universities – especially in New Delhi – are now also regularly part of the seminars and conferences organized by think-tanks both in India and abroad and often write for publications produced by these think-tanks.[25] The chosen few are also part of various Indian government initiatives such as, for example, the National Security Advisory Board (NSAB) or on the governing councils/executive boards of government think-tanks such as the IDSA. The process in India, however, does not seem to have picked up the necessary urgency to produce the resources required by a rising global power, and compares poorly to similar efforts in China, or to efforts to study China itself in the United States, for example.[26]

The expression ‘academics’ as employed thus far has only taken into account those in the area studies/international relations field. There is another group of academics/scientists/researchers who exist outside this field that works and interacts frequently with its Chinese counterparts. This sub-group usually includes development economists, agricultural scientists, sociologists, and the like, to whom, the strategic/military aspect of the relationship between India and China is more often than not, simply irrelevant. Examples include such think-tanks or research institutions as the Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS)[27] and the National Institute of Science, Technology and Development Studies (NISTADS)[28], both in New Delhi. This group of Indians travels frequently to China on many joint projects, funded by either or both governments or by a number of international agencies[29] – in fact, many senior scholars of this group probably travel more often than their counterparts in the area studies/international relations field. Despite their wide exposure to China however, this group can be extremely naïve about even the rudimentary features of Chinese culture and society or if they do develop an idea of the diversity of China over time – which after all can often also be gleaned from the data they work with – they can still be ignorant of the politics of China, including the politics of interviews, case study selection, data choice, data interpretation and the like.

Still, this group perhaps because of its naiveté can also be the best ambassadors for pushing an alternative manner of engagement with China and of fresh ways of looking at and learning from China. In this sense, the Indian government has probably stumbled on – for it is rather difficult to say that such a result was actually intended by either the bureaucrats or politicians in India – a mode of improving Sino-Indian relations. That said, this sub-group will no doubt, over time and with greater exposure to China, begin to note the discrepancies and shortcomings of their work involving China, and learn to highlight challenges that go beyond merely problems of communication and food.

The Political Class

In addition to these four groups, a fifth group exists, namely the political class. This group had been dominant following Independence led as it was by Jawaharlal Nehru, who was Prime Minister and External Affairs Minister concurrently. The two parties that have the most significant experience of national governance, namely the Congress (I) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), do have their particular positions on Sino-Indian relations as do the Left parties. However, since the beginning of the coalition era in Indian politics, a different breed of politicians has reached the helm of affairs, familiar and concerned more with domestic political arithmetic than with foreign policy calculations. Indian politicians and ministers (including a few Prime Ministers and Foreign and Defence Ministers) have been content largely to take their cue from ‘experts’ (read civilian bureaucrats) for their views on foreign policy and geopolitics, including Sino-Indian relations.[30]

As only one among a group of people trying to create and influence a China policy in India, politicians are in neither aspect actually quite successful or active by themselves (Ranganathan and Khanna 2004: 168-170).[31] Still by the powers vested in them as representatives of the people, there is also reason to argue that politicians whether of the Congress (I) or the BJP or the regional parties, are also among the most open to listening to opposing views and exploring different options on Sino-Indian relations than the vast majority of either government officials or academics.

Indian businesses and traders

A sixth set of actors include Indian businesses and traders. Their influence has certainly grown in the last decade alongside India’s economic growth even if they are not yet widely adept at or interested in expressing an opinion on China. The extent of their influence is seen in their vocal opposition to the dumping of Chinese goods and to a Free Trade Agreement proposed by the Chinese in the early 2000s. Indian big businesses and various chambers of industry have also repeatedly complained about non-tariff barriers to Indian investments in China.[32]

While by and large, this community takes its cue on political matters from the other groups mentioned above, it needs to be noted that the impact of economic linkages with China has already been visible on the Indian political system. For instance, the Bellary brothers of Karnataka, political heavyweights and for a time kingmakers in the state unit of the BJP, built their fortunes and political careers on the back of the iron ore trade with China.[33] Similarly, the decision of the Indian government in 2011 to allow Indian companies to avail of renminbi loans may be seen as benefitting several Indian infrastructure majors (Hindu 2011). Whether such a decision has economic merit or not is perhaps a separate question, but the issue is noteworthy from a political standpoint when examined against the backdrop of constant denials of permission to Chinese companies to operate in India on ‘security’ grounds.

Concerns about big businesses influencing government policy in the direction of lowering its guard against security concerns from China were expressed in some quarters when in July 2012, Ratan Tata, scion and head of one India’s largest and most respected business enterprises, ventured to declare that he wished India could ‘use China as a very strong ally, to forge a relationship with China which would be a sustaining one’ (Rediff.com 2012). Tata was accused of lacking a clear understanding of the many dimensions and nuances of the Sino-Indian relationship and of focusing on a simple calculation of profit (Vembu 2012). In what might become an increasingly familiar exercise for Indian strategic analysts, the Tata group’s many business interests in China were detailed in order to explain Ratan Tata’s motivations for making the statement he did (Vembu 2012). This by itself suggests that Indian businesses will increasingly be vocal in determining the direction of the country’s economic policy vis-à-vis China. The flip side of this influence is that given Indian big businesses are also entering the defence industry sector, an influential military-industrial complex can also very well see advantages in the hardening of positions against China.

With both trade volumes and the number of such businesses increasing, however, it is inevitable that problems will arise with consequences for Sino-Indian relations. The incidents of kidnapping against Indian traders in China in 2012 over non-payment of dues are a case in point (Krishnan 2012). Given that these traders come from across a wide swathe of India and are often the only linkage or window to China that their localities have, local politicians could also get involved in raising questions about or driving resentment against China – another factor that policymakers in New Delhi will have to take into account.

The general public

The general public brings up the bottom of the list as the seventh actor involved in Sino-Indian relations. The reason why the public forms an important category is because one, they should in any democratic dispensation and two, they can, by their attention or lack thereof to foreign policy and security issues, affect the priorities of the political class. The Indian public too, takes its cue from the other groups and tends to fall into one of two camps – either the ultra-nationalists or the pragmatists. While it is easy to characterise public interest in foreign policy matters as too broad or too shallow to count for much or as bordering on disinterest, this is not true particularly where India-Pakistan relations are concerned and to a lesser extent in the case of Sino-Indian ties. Rather, while this group is prone to being aroused by shrill media coverage of alleged Chinese incursions across the LAC for example, it is probably just as likely to demand a pragmatic get-on-with-it approach on China with time, and ask that the government and the media concentrate on more pressing everyday issues affecting ordinary people.

Even though officially sponsored exchange of students between the two countries comprises extremely small numbers, there has been an explosion in recent years of students from India headed to China – literally, in the thousands – to obtain professional degrees particularly in medicine because the costs of tuition are considerably cheaper (Bhattacharyya 2012).[34] That said, it remains too soon to say how effective a voice these students will be in Sino-Indian relations or even if their presence can at all times be a force for good. It must be noted in this context, that education and/or middle class status are no bar for Indians to continue to hold ignorant or prejudiced views on China and on the Sino-Indian relationship. That said, this seventh group is likely to become, with time and growing exposure to the outside world, an increasingly better-informed and powerful factor in Indian foreign policymaking.

INDIAN THINKING ON CHINA: ITS OPERATION AND CONSEQUENCES

The presence of different lines of thinking or of various actors and interest groups contributing their views on China does not by itself constitute a ‘strategic’ perception of China nor does it have to result in ‘strategic’ thinking and planning on China. Competing influences and multiple actors are, in fact, as likely to lead to policy mistakes as the lack of them. By ‘strategic thought’ is assumed, on the one hand, the ability to consider alternative or contending viewpoints to reach a coherent policy for a given situation or a possible future scenario. On the other hand, no matter what potential scenarios have to be accounted for, political systems, particularly democracies, have to also meet short-term interests and considerations of contending actors both within and outside government. ‘Strategic thought’ therefore, in a democracy like India, must necessarily be different from what goes under that name in one-party or authoritarian political systems.

There can be a similarity of national interest goals brought about by size, demography, or the international political context, but the nature of their domestic politics and economy among other things, are just as likely as geography and history, to contribute to a wholly different menu of strategic thought, interests and choices. Thus, India and China, both capable of identifying themselves as Third World countries and as being opposed to a unipolar world order, can also identify themselves with or against that same sole superpower on various issues and often in opposition to each other.

What then is the substance of India’s strategic thinking with respect to China and how does this inform the country’s foreign, defence and security thinking? How coherent and well-thought out is this strategic thinking? And how successful has it been in achieving Indian national interest vis-à-vis China? These, then, are the questions that Indian strategic thinkers confront, debate, discuss and often disagree on.

What is defined as ‘strategic’ can depend on who the chief actors are and their specific corporate interests. It is reasonable to expect that government leaders will (or should) view holistically the threat or challenge – as the case may be – posed by China, and draw up their objectives and strategies accordingly. This is a reasonable expectation to have but attributing reasonableness to the government or its agencies is one thing – constraints of resources and competing domestic priorities can combine to keep them from carrying out the necessary actions and perhaps from making even statements of intent. The wider strategic community outside of the four walls of government need not and often do not exercise such restraint in their advice to the government on China policy.

This section will therefore attempt to differentiate what the government might possibly think from what is seen in the discussions on China in the wider Indian strategic community. The fundamental question examined here is of how India actually engages with China and the challenges it poses.

Boundary Dispute and Economic Ties

Neighbours cannot be wished away and we must live with them. As a country larger than India in size, economic and military resources, and political clout, it would be impossible to aim for anything other than a peaceful and stable relationship with China. This must be seen as a rational and perhaps, the foremost of India’s strategic objectives. Once this objective is acknowledged – and as evident from the narrative above, it is not always the case that elements within the Indian strategic community agree on this objective – there are several ways to interpret what is meant by the expressions ‘peaceful’ and ‘stable’ and what methods can be used to achieve the objective.

But to start first with those who think no compromise with China is possible given the history of its aggression against India,[35] playing the ‘Tibet card’ is a much favoured option (Chellaney 2012b). The idea is to support the Tibetan government-in-exile and Tibetan independence openly. On occasion there are calls also for greater more open political engagement with Taiwan – the demand for a tit-for-tat policy when China disputes Indian sovereignty over Kashmir or over Arunachal Pradesh. That Tibet and Taiwan form part of China’s ‘core’ national interests – that is, issues over which China will not hesitate to go to war – does not seem to bother this group of thinkers. If war is the end result of any thinking and consequently planning on China, then it is difficult to rationalise calling such thinking ‘strategic’ – unless, of course, the result is a clear-cut military and political victory over China but which, however, looks an unlikely scenario for the foreseeable future. However, advocates of such hard-line thinking on China – by and large a minor and dwindling group – do not ever give the impression of having considered the consequences of a possible conflict arising out of the implementation of their policies (Shourie 2009).[36]

Meanwhile, both the pragmatists and the pacifists are clear that the eventual resolution of the Sino-Indian boundary dispute will involve compromises, including the give-and-take of territory (Ranganathan and Khanna 2004: 166-170; Mohan 2003: 165-66; Saran 2011; Noorani 2002). Nevertheless, there are differences too, among those who advocate peace and stability with China in terms of the approaches to be used. How can India cope with the rapid Chinese military modernisation and increasing gaps in capabilities elsewhere with China? In other words, many pragmatists who see the eventual object as India overtaking China in the economic and military spheres, seek also to ensure the Chinese on good behaviour in the region and globally. The pragmatists here are divided in terms of the relative weight they give to different options. Some emphasise mostly military options, others suggest continuing stress on military preparedness while simultaneously pursuing closer economic cooperation with China (Banerjee 2010; Saran 2012) and yet others emphasise economic cooperation above all in the belief that it is this pursuit alone that can both stabilise India and China internally and eventually create conditions for peaceful coexistence (Sanwal 2012).

The first line includes such measures as continuing Indian military modernisation and the pursuit of closer ties with the United States and with China’s neighbours that too, have reasons to be concerned about Chinese growing political and economic clout and its rapid military modernisation. The second and third sub-groups can also use such ultra-nationalist pet themes as Tibet more constructively by suggesting that New Delhi could put the boundary dispute aside for the moment and use China’s Western Development Strategy in Tibet and Xinjiang as a means of both improving economic conditions on the Indian side of the border while also creating new constituencies of support for India both in these provinces and in China as a whole (Jacob 2011: 135-148; Mohan 2003: 171). Similarly, on Taiwan, given that cross-Straits trade has increased continuously since the beginning of economic reforms in China despite the political complications, these pragmatists argue there is no reason why India should not also more actively pursue economic and technology cooperation with the Taiwanese (Mohan 2003: 163; Jacob 2007). On Taiwan, the first sub-group would also go so far as to advocate intelligence-sharing and frequent consultations on matters of military interest.[37]

While not necessarily connected to Indian business interests, the general position that pragmatists take in favour of closer economic ties with China has coincided with the positions of Indian businesses particularly those involved in heavy physical infrastructure development, manufacturing and telecom enterprises. On the other hand, problems in the Sino-Indian economic relationship – dumping, non-tariff barriers (Bery 2011), and a skewed trade basket for example[38] – all of which have resulted in a rising Indian trade deficit and which do not at the moment have a solution in sight, probably undercut the arguments of those who suggest that economics plays a positive role in Sino-Indian ties (Bhattacharya 2010: 678).[39]

India’s National Security Advisor (NSA), Shivshankar Menon has, however, argued against the inevitability of the two countries becoming strategic adversaries and has stated that he found ‘such determinism misplaced’ highlighting both the successful experience of both governments over the decades ‘in managing their differences and building on commonalities’ and the wisdom of their leaders that has allowed problems to be handled ‘in a mature manner’ (Menon 2012).[40]

Regional and Global Engagement

Across all three groups, there can be wariness or skepticism about reliance on the West, particularly on too close a relationship with the United States, as a way of India maintaining balance with China and hence there is simultaneously support especially among the pragmatists and the pacifists – to varying degrees, of course – for such Indian multilateral engagement involving China as the Russia-India-China (RIC) trilateral or the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS). This can arise from various factors ranging from a memory of the experiences of the Cold War and a related desire to maintain strategic autonomy (so clearly evident in the Indian strategy document, Non-Alignment 2.0 (2012)) to a distrust of the United States’ intentions – notable among left-leaning academics to the real possibility of achieving common objectives (Varadarajan 2009; Sreenivasan 2011).

While both these groupings involve China, there are also global groupings that India is involved in that do not involve China such as the India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA) and therein lies one of the strategic ambiguities of India’s China policy – does India consider democracy or political ideology as an important element of its strategic thinking vis-à-vis China? In a speech made just a couple of months before he took over as the NSA, Shivshankar Menon advocated ‘a realist policy leavened by our ideals.’ While the immediate reference was to achieving progress in the goal of domestic transformation, the remark came in a speech outlining his experience as Foreign Secretary, leaving us perhaps with a sense of one of the ways in which pragmatism is shaping up within the government. That said, it has so far, been difficult to identify among Indian strategic thinkers in general, any genuine commitment to using democracy as a tool of policy when it comes to China – in terms of building an alliance of democracies in the Asia-Pacific for example,[41] leave alone in terms of promoting India as an example of a functioning Third World democracy.[42]

Those of the ultra-nationalist camp do occasionally raise the subject of China being an authoritarian state and its repression of Tibetans and of Buddhism as sticks to beat China with but the positions especially of the religious rightwing on other issues of Indian national concern such as on minorities, or continued indifference to social injustice in the form of caste oppression, including opposition to affirmative action policies of the government, suggest that their own commitment to democracy and pluralism is partial at best. Pragmatists, by definition, go with what works in a given situation while the pacifists, particularly those that lean left argue that using democracy in relations with China tends towards an exercise in hegemony and is irrelevant when the most important issues that concern China and India are socioeconomic ones. Both pragmatists and the pacifists also note that given India’s treatment of ethnic and religious minorities, and the use of state violence rather than political dialogue against ethnic secessionist and left-wing extremist movements means that the use of ‘democracy’ as a foreign policy tool vis-à-vis China as mentioned above or more generally – in the sense of democracy promotion or armed intervention in support of democracy – can turn into a liability.

To return to the subject of regional cooperation, however, pragmatists can espouse regional forums both without Chinese involvement such as the Mekong-Ganga Cooperation Initiative (GMCI) and the Bangladesh-India-Myanmar-Sri Lanka-Thailand Economic Cooperation (BIMST-EC), as well as those involving China like the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Regional Economic Cooperation Forum (BCIM, formerly the Kunming Initiative), as additional vehicles for promoting Indian interests at the regional level. The same considerations can apply to IBSA at the global level (Singh 2007; Mohan 2003: 156-58; Jacob 2012).[43]

Pragmatists also understand that economic competition and increased Chinese presence in India’s South Asian neighbourhood are inevitable and they rely on Indian economic expansion supported by the private sector as one major prong of their efforts to match China and to possibly help build a greater commonality of interests between the two countries (Singh 2005; Mohan 2010; Baru 2011; Das 2011). On the whole, pragmatists who dominate the Indian government try to project the view that the competition between India and China is ‘exaggerated’ and that ‘there is enough space for both India and China to realise their development aspirations’ (Amb. Jaishankar quoted in Krishnan 2011). They also suggest that India might copy China in this regard to promote its own ‘national prosperity, regional clout and international standing’ (Mohan 2001). Meanwhile, on a range of non-traditional security issues, such as energy security and maritime security seen in particular by many sections of the Indian strategic community as possible points of bilateral friction, the government views these as potential areas of cooperation and as possible grounds for creating an Asia-wide security architecture (Menon 2012).

Henderson Brooks-Bhagat Report

Meanwhile, despite the increasing coalescing of and consensus around pragmatic approaches to dealing with China, there remains in Indian strategic thinking about the northern neighbour a substantial confidence-deficit. Indeed, no study of Indian thinking on China can be complete without examining the fears that affect both the Indian government and non-government affiliated strategic thinkers.

One example, and a classic one at that, will suffice. The Operations Review Committee Report on the 1962 War by Lt. Gen. T.B. Henderson Brooks and Brig. P.S. Bhagat that has not been released till date, 50 years after the debacle. What explains this reluctance? In a March 2009 order turning down veteran journalist Kuldip Nayar’s application for a copy of the Report under the provisions of the Right to Information, a two-member Bench of the Central Information Commission, declared on the basis of a submission from the Director General Military Operations that ‘[d]isclosure of this information will amount to disclosure of the army’s operational strategy in the North-East and the discussion on deployments had a direct bearing on the question of the Line of Actual Control between India and China, a live issue examination (sic) between the two countries at present’ (Noorani 2012).

Later in April 2010, Indian Defence Minister A. K. Antony would similarly declare in Parliament, that the contents of the Report ‘are not only extremely sensitive but are of current operational value’ (Vembu 2010). Is it the case that political sensitivities particularly of the Congress (I) and its desire to prevent any further damage to the reputation of Nehru is stopping the release of the Report? If so, why did non-Congress (I)-led governments, at various points not release the report? This speaks then perhaps not so much of political reluctance alone as also perhaps bureaucratic/military reluctance. But, if a report some 50 years old continues to be relevant to Indian operational requirements along the LAC, then it must point to a lack of progress in military terms from the conditions of 1962 – and this can be corroborated by the continuing poor state of physical infrastructure along the LAC. Thus, Neville Maxwell, one of those who it is believed has seen the Report in full, has noted that ‘there is nothing in it concerning tactics or strategy or military action that has any relevance to today’s strategic situation’ (Vembu 2010).

Two facets of Indian strategic thinking on China suggest themselves in the continuing saga over the release of the Henderson Brooks-Bhagat Report. One, to come back to a point made earlier – and this could apply to India’s thinking on foreign policy in general – the government, including both the politicians and officials, lacks faith in the ability of the people to judge for themselves on matters related to China and the Sino-Indian boundary dispute. Two, if secrecy is necessary because the government remains unable despite the passage of time, to overcome completely the hurdles – physical and bureaucratic – that led to the defeat in the first place, then the government does not wish to advertise this lack of progress and its inabilities. Together, a politico-bureaucratic nexus combines to keep public viewpoints and impact on government policymaking at a minimum. The running battle between the government and the media over the latter’s admittedly sensationalist and often misinformed reportage over alleged LAC incursions by Chinese troops is part of the same problem.

Conclusion

The people involved in strategic thinking and who are also simultaneously influential in shaping China policy in India belong to different lines of thinking in terms of their views of and attitudes towards China but broadly agree that the structure of the regional and global order demands both preparation against any Chinese hostility whether by word or by deed, and engagement to ensure that China, the larger power, remains also a ‘responsible’ power. In other words, China can be friend or foe depending on the situation or issue at stake but is, at all times, a competitor.

There is an appreciation of India’s weaknesses in its dealings with China – not so much because of the latter’s size, geography or demography – but because processes in the Indian political system require priorities elsewhere, to be addressed first. These can be developmental priorities – ironically, something that the Chinese themselves stress in their relations with the rest of the world – or priorities dictated by perceptions of the world outside India’s borders. Here, for all the attention that the rise of China has received elsewhere in the world, and particularly in the United States and in India’s extended neighbourhood in Southeast Asia, attention of the vast majority of Indians, in so far as they relate to foreign policy, remains focused firmly on the west, whether Pakistan or the Occident. Thus, there is in fact, a neat mirror image of attention that ordinary Chinese give India, which is next to nothing in comparison to the focus they have on their neighbours to the east such as Japan and the United States.

Thus, Indian policymakers led by the political class cannot help but acknowledge these two domestic realities and China as a consequence receives far less priority than other subjects that exercise the government. A relative judgment, perhaps, cannot be made in the sense of framing this as ‘far less priority than it deserves’ because as a developing nation with huge internal challenges, foreign policy is only one of many priorities for the country’s leaders. But even within foreign policy, as long as the border remains largely peaceful, and China remains largely a black box in the Indian imagination, India’s northern neighbour will not receive much attention.

Indian ‘strategic’ thinking on China is therefore, probably premised on the wrong foundations. Strategic thinking does not start with the fact of enmity with a country and therefore, the need to pay attention to that country – as is the case with most thinking on China in India, today.[44] It needs to be based on the structural realities of the world order – and these are realities that both policymakers and the voters need to be aware of in order to think rationally and deal effectively with China. Thus, a resolution of the boundary dispute does not by itself guarantee peaceful relations with China. Rather, additional issues are likely to crop up between the two countries – economic conflict at the micro-level of Indian businessmen being roughed up in Chinese trading towns and at the macro-level of competition for energy resources, are cases in point.

To aid strategic thinking in such contexts, Indian strategic analysts must give up the idea that China can be studied or dealt with in a purely bilateral or regional context or in generic terms. Thus, in so far as a cognisance of structural realities of the world order are necessary to situate the true extent of the China ‘challenge’ to India, the next step requires specific, focused and unremitting attention to the study of China in all its facets. Absent such comprehensive study of China in the country’s universities, think-tanks, and government establishments, Indian strategic thinking on China will remain weak and uncomprehending of the extent and seriousness of the challenges posed by China.

REFERENCES

‘ABPS Report 2010 Eng,’ Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, no date, http://www.rss.org//Encyc/2012/10/22/ABPS-REPORT2010-ENG.aspx (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Adityanjee, A. 2012. ‘Military Bases with Chinese Characteristics,’ CLAWS Article, No. 2053, 20 January, http://www.claws.in/index.php?action=master&task=1054&u_id=144 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Advani, L. K. ‘Speech by Shri L. K. Advani at Sixth International Conference of Tibet Support Groups at Surajkund – Haryana,’ Bharatiya Janata Party, 5 November 2010, http://www.bjp.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=6431:speech-by-shri-lk-advani-at-sixth-international-conference-of-tibet-support-groups-at-surajkund-haryana&catid=69:speeches&Itemid=495 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Anand, Vinod. 2012. ‘The Evolving Threat from PLA along Indo-Tibetan Border: Implications,’ Articles, 26 July, Vivekananda International Foundation, http://www.vifindia.org/article/2012/july/26/the-evolving-threat-from-pla-along-indo-tibetan-border-implications (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Banerjee, Dipankar. 2010. ‘India-China Relations: Negotiating a Balance,’ IPCS Issue Brief, No. 160, December, http://www.ipcs.org/pdf_file/issue/IB160-Banerjee-India-China.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Baru, Sanjaya. 2011. ‘Asian drama,’ Business Standard, 7 March, http://www.business-standard.com/india/news/sanjaya-baru-asian-drama/427468/ (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Bery, Suman. 2011. ‘The India-China Strategic Economic Dialogue,’ East Asia Forum, 26 September, http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2011/09/26/the-india-china-strategic-economic-dialogue/ (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Bhadrakumar, M. K. 2009. ‘Challenges for Indian foreign policy,’ Hindu, 6 March, http://www.hinduonnet.com/2009/03/06/stories/2009030656301000.htm (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Bhattacharya, Abanti. 2010. ‘Sixty Years of India-China Relations,’ Strategic Analysis, Vol. 34, Issue 5.

Bhattacharyya, Rica. 2012. ‘Lured by cheaper fee structure, wannabe medicos opt Chinese medical colleges,’ Economic Times, 17 August, http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-08-17/news/33249708_1_medical-colleges-private-colleges-aspiring-medical-students (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Chansoria, Monika. 2011. ‘China’s Infrastructure Development in Tibet: Evaluating Trendlines,’ Manekshaw Paper, No. 32, 2011, CLAWS, http://claws.in/administrator/uploaded_files/1317312941MP%2032%20inside.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Chellaney, Brahma. 2012a. ‘Lasting lesson of 1962: don’t be caught off-guard again,’ Times of India, 22 January, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-01-22/all-that-matters/30652464_1_premier-zhou-paracel-islands-chinese-aggression (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Chellaney, Brahma. 2012b. ‘Let facts speak for themselves on India-China border,’ Sunday Guardian, 1 November, http://www.sunday-guardian.com/analysis/let-facts-speak-for-themselves-on-india-china-border (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Chellaney, Brahma. 2011. ‘Water is the new weapon in Beijing’s armoury,’ Financial Times, 30 August, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/4f19a01e-d2f1-11e0-9aae-00144feab49a.html (accessed on 25 November 2012).

‘China a second class enemy; could be a strong ally: Tata’, Rediff.com, 9 July 2012, http://www.rediff.com/news/slide-show/slide-show-1-china-a-second-class-enemy-could-be-a-strong-ally-ratan-tata/20120709.htm (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Das, R. N. 2011. ‘Sino-Indian Trade: Smoothening the Rough Edges,’ IDSA Comment, 27 September, http://www.idsa.in/idsacomments/SinoIndianTradeSmootheningtheRoughEdges_rndas_270911 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Dutta, Sujit. 2008. ‘Revisiting China’s Territorial Claims on Arunachal,’ Strategic Analysis, Vol. 32, Issue 4, pp. 549-581.

Jacob, Jabin T. 2012. ‘India’s China Policy: Time to Overcome Political Drift,’ RSIS Policy Brief, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Singapore, June, http://www.rsis.edu.sg/publications/policy_papers/Time%20to%20Overcome%20Political%20Drift.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Jacob, Jabin T. 2011. ‘For a New Kind of ‘Forward Policy’: Tibet and Sino-Indian Relations,’ China Report, Vol. 47, No. 2, May, pp. 135-148.

Jacob, Jabin T. 2007. ‘India-Taiwan Relations: In Delicate Minuet,’ IPCS Article, No. 2322, 27 June, http://www.ipcs.org/article/india-the-world/india-taiwan-relations-in-delicate-minuet-2322.html (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Khilnani, Sunil, Rajiv Kumar, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Prakash Menon, Nandan Nilekani, Srinath Raghavan, Shyam Saran and Siddharth Varadarajan. 2012. Nonalignment 2.0: A Foreign and Strategic Policy for India in the Twenty First Century. National Defence College and Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, http://www.cprindia.org/sites/default/files/NonAlignment%202.0_1.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Krishnan, Ananth. 2012. ‘In Chinese trading town, disputes and strains fuel mistrust of India,’ Hindu, 5 January, http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/in-chinese-trading-town-disputes-and-strains-fuel-mistrust-of-india/article2775310.ece (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Krishnan, Ananth. 2011. ‘Competition with China ‘exaggerated,’ says Indian envoy,’ Hindu, 16 December, http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/article2720741.ece (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Menon, Shivshankar. 2012. ‘Speech by NSA on ‘Developments in India-China Relations,’ Speeches & Statements, The Chinese Embassy, New Delhi, 9 January, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India,’ 9 January, http://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/17101/Speech+by+NSA+on+Developments+in+IndiaChina+Relations (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Mohan, C. Raja. 2010. ‘Diplomacy for the new decade,’ Seminar, No. 605, January, http://www.india-seminar.com/2010/605/605_c_raja_mohan.htm (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Mohan, C. Raja. 2009. ‘The Middle Path,’ Indian Express, 30 September, http://www.indianexpress.com/news/the-middle-path/522993/0 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Mohan, C. Raja. 2003. Crossing the Rubicon: The Shaping of India’s New Foreign Policy. New Delhi: Viking

Mohan, C. Raja. 2001. ‘Trade as strategy: Chinese lessons,’ Hindu, 16 August, http://www.cscsarchive.org:8081/MediaArchive/audience.nsf/(docid)/5A76765C75707554E5256ADB001C6F09 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Noorani, A. G. 2012. ‘Publish the 1962 war report now,’ Hindu, 2 July, http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/article3591887.ece (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Noorani, A. G. 2002. ‘On Sino-Indian relations,’ Frontline, Vol. 19, Issue 1, 5-18 January, http://www.flonnet.com/fl1901/19010770.htm (accessed on 25 November 2012).

‘Now, India Inc can borrow in Chinese currency,’ Hindu, 15 September 2011, http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/industry-and-economy/banking/article2456360.ece (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Parthasarathy, G. 2012. ‘We didn’t really learn from the debacle of 1962,’ New Indian Express, 28 October, http://newindianexpress.com/magazine/voices/article1313007.ece (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Raman, B. 2012.‘The Jugular Reality: India’s Strategic Debate,’ Chennai Centre for China Studies (C3S), Paper No. 990, 6 June, http://www.c3sindia.org/india/2932 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Rajagopalan, Rajeswari Pillai and Kailash Prasad. 2010. ‘Sino-Indian Border Infrastructure: Issues and Challenges,’ ORF Issue Brief, No. 23, August, http://orfonline.org/cms/export/orfonline/modules/issuebrief/attachments/Ib_23_1283150074942.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Ranganathan, C. V. and Vinod C. Khanna. 2004. India and China: The Way Ahead. New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications.

Roy, Bhaskar . 2011. ‘China Projecting India Threat And Limiting India: The Game Goes On – Analysis,’ SAAG, 3 May, http://www.southasiaanalysis.org/paperindex.asp?currentpage=26 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Sanwal, Mukul. 2012. ‘The 50th Anniversary of the Border Conflict with China: A Strategic Analysis,’ IDSA Comment, 19 October, http://idsa.in/idsacomments/The50thAnniversaryOfTheBorderConflictWithChinaAStrategicAnalysis_MukulSanwal_191012 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Saran, Shyam. 2012. ‘Lesson from 1962: India must never lower its guard,’ Times of India, 11 October, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Lesson-from-1962-India-must-never-lower-its-guard/articleshow/16760000.cms?intenttarget=no (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Saran, Shyam. 2011. ‘Neighbours only since 1950,’ Indian Express, 12 January, http://www.indianexpress.com/news/neighbours-only-since-1950/736322/0 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Shourie, Arun. 2009. ‘Digging our head deeper in the sand,’ Indian Express, 7 April, http://www.indianexpress.com/news/digging-our-head-deeper-in-the-sand/443896/0 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Sibal, Kanwal. 2012. ‘Games China Plays – India’s Insecurities allow China to get its Own Way,’ Articles, 19 October, Vivekananda International Foundation, http://www.vifindia.org/article/2012/october/19/games-china-plays-indias-insecurities-allow-China-to-get-its-own-way (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Singh, Swaran. 2012. ‘Russia-India-China Strategic Triangle: Signalling a Power Shift?’ IDSA Comment, 19 April, http://idsa.in/idsacomments/RussiaIndiaChinaStrategicTriangle_ssingh_190412 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Singh, Swaran. 2007. ‘Mekong-Ganga Cooperation Initiative: Analysis and Assessment of India’s Engagement with Greater Mekong Sub-region,’ IRASEC Occasional Paper, No. 3, 15 August, http://www.jnu.ac.in/Faculty/ssingh/Mekong-Ganga.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Singh, Swaran. 2005. ‘China-India Bilateral Trade: Strong Fundamentals, Bright Future,’ China Perspectives, 62 November-December, http://chinaperspectives.revues.org/2853 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Sreenivasan, T. P. 2011. ‘New five make right noise,’ New Indian Express, 26 April, http://expressbuzz.com/biography/new-five-make-right-noise/269200.html (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Stobdan, P. 2008. ‘Can India ever Trust China?,’ IDSA Comment, 27 October, http://idsa.in/idsastrategiccomments/CanIndiaeverTrustChina_PStobdan_271008 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Stobdan, P. 2010. ‘Is China Desperate to Teach India Another Lesson?’ Strategic Analysis, Vol. 34, Issue 1, pp. 14-17.

Varadarajan, Siddharth. 2011. ‘Eastern promises, western fears,’ Hindu, 25 January, http://www.hindu.com/2011/01/25/stories/2011012563281200.htm (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Varadarajan Siddharth. 2010. ‘Trading one hyphen for another,’ Hindu, 11 November, http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/article952529.ece?homepage=true (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Varadarajan, Siddharth. 2009. ‘The Russia–India–China Trilateral and Afghanistan,’ China Report, May, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 153-158.

Vembu, Venky. 2012. ‘China as India’s ally: Why Ratan Tata is wrong,’ FirstPost, 10 July, http://www.firstpost.com/world/china-as-indias-ally-why-ratan-tata-is-wrong-373302.html (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Vembu, Venkatesan. 2010. ‘The ghost of 1962,’ DNA, 2 May, http://www.dnaindia.com/india/report_the-ghost-of-1962_1377901 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

Verma, Bharat. 2010. ‘China’s New Cold War,’ Organiser, 24 October, http://www.organiser.org/dynamic/modules.php?name=Content&pa=showpage&pid=367&page=8 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

NOTES

* The author would like to thank an anonymous referee for useful comments on an earlier draft of this chapter. The author also thanks Rekha Chakravarti and Alka Acharya for detailed critiques and valuable help on strengthening the arguments made in this chapter. The final responsibility for the views expressed and for any mistakes is the author’s alone.

[1] Whether it actually understands Pakistan in any useful manner – that is, in the sense of achieving a permanent peace with it – is of course another matter. It is possible, of course, that it is because India views Pakistan in a way that mixes both prejudice and familiarity that it can also be restrained in its behaviour towards that country. For example, neither the Parliament attack of 2001 nor the Kaluchak massacre of 2002 or the 26/11 Mumbai attacks in 2008, to name three prominent terrorist provocations in the last decade, led India into armed conflict with Pakistan. And this is true despite massive and long-drawn Indian military mobilisation in response to the first provocation. At the same time, it might also be increasingly the case that India no longer finds it useful politically or strategically to get into an armed conflict with Pakistan.

[2] This classification makes no claim to originality and borrows in various ways from other broad classifications of schools of thought within Indian foreign policy, such as from Kanti Bajpai (2002), ‘Indian Strategic Culture,’ in Michael R. Chambers (ed.), South Asia in 2020: Future Strategic Balances and Alliances, Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, pp. 245-304. Bajpai also discusses how his three schools – Nehruvianism, neoliberalism, and hyperrealism – perceive grand strategy with respect to China (pp. 266-273). There are several other notable classifications of Indian thinking on or perceptions of China. Amitabh Mattoo has outlined four types of Indian images of China – ‘ancient friend and modern ally,’ ‘role model,’ ‘unpredictable adversary and dangerous rival,’ and, ‘inscrutable and mysterious.’ He also suggests in passing two broader categories of ‘apologists for China’ and ‘so-called China-baiters.’ See Amitabh Mattoo, “Imagining China,” in Kanti Bajpai and Amitabh Mattoo (eds) (2000), The Peacock and the Dragon: India-China Relations in the 21st Centrury (New Delhi: Har-Anand, 2000), p. 16. Mohan Malik categorizes India’s China observers into hyperrealists, pragmatists, and appeasers, while Steven Hoffman’s divides Indian perceptions of China as ‘China is hostile’, mainstream, and ‘China is not hostile’. See respectively Mohan Malik (2003), ‘Eyeing the Dragon: India’s China Debate,’ in Satu P. Limaye (ed.), Asia’s China Debate, Honolulu, Hawaii: Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, http://www.apcss.org/Publications/SAS/ChinaDebate/ChinaDebate_Malik.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2012) and Steven A. Hoffman (2004), ‘Perception and China Policy in India,’ in Francine R. Frankel and Harry Harding (eds), The India-China Relationship: What the United States Needs to Know, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 33-74. For another classification of thinking on China (hawkish, pragmatic and pacifist), see, Bhartendu Kumar Singh (2011), ‘India-China Relations: Rising Together?’ in D. Suba Chandran and Jabin T. Jacob (eds), India’s Foreign Policy: Old Problems, New Challenges, New Delhi: Macmillan, pp. 35-37. Rahul Sagar (2009) makes another interesting general classification of Indian foreign policy thinkers as moralists, Hindu nationalists, strategists, and liberals. See Rahul Sagar (2009), ‘State of mind: what kind of power will India become?’ International Affairs, Vol. 85, No. 4, pp. 801–816. See also B. Raman (2012), ‘The Jugular Reality: India’s Strategic Debate,’ Chennai Centre for China Studies (C3S), Paper No. 990, 6 June, http://www.c3sindia.org/india/2932 (accessed on 25 November 2012).

[3] Indeed, what is defined as ‘strategic thought’ in Third World countries, might be a different creature altogether from standard Western understanding of the term – in terms of conceptions of time, of other peoples and cultures, and of ultimate national objectives. For instance, national pride or the ‘rightness’ of a position might be seen in Asia as far more important objectives than absolute assurance of physical security vis-à-vis a rival. George Tanham has also, for example, noted that ‘the lacunae and ambiguities [of Indian strategic culture] … seem more confusing to Westerners than to Indians, who accept the complexities and contradictions as part of life.’ Tanham (1992), Indian Strategic Thought: An Interpretive Essay, Santa Monica, California: Rand, p. v.

[4] Naturally, the implication is that the pragmatists can be dismissive or at the very least skeptical of the abilities of the other camps to define Indian national interests rationally.

[5] In other words, for example, ultra-nationalists on Pakistan could well be pragmatists when it comes to China.